Odd Behaviors - Understanding Why The Autistic Child Does What He Does...

Spinning and Visual Stims…

What's The Fascination With This Activity For The Autistic Child?

If there was one thing that was characteristic of the autistic child, especially in earlier years, when autism first surfaced, it surely was the love of spinning things.

Zachary indeed loved to spin if given the opportunity. In addition to spinning, there were other activities that parents had also come to describe as "visual stims"... such as a child moving a pencil rapidly back and forth in front of his face. Spinning and other activities so often referred to in the past as “visual stims”, I believed, were basically one and the same. I will therefore, discuss spinning specifically in this example, although the concept was equally applicable to other “visual stims” as well.

What was it about spinning that was so intriguing to the child with autism? The answer could be traced back to the issue of the "partial" verses the "whole.

There were many parents and professionals who believe that spinning was simply a way to get a visual stimulation. If that were the case, spinning would not continue once eye contact with the spinning object was broken. That, however, was clearly not the case.

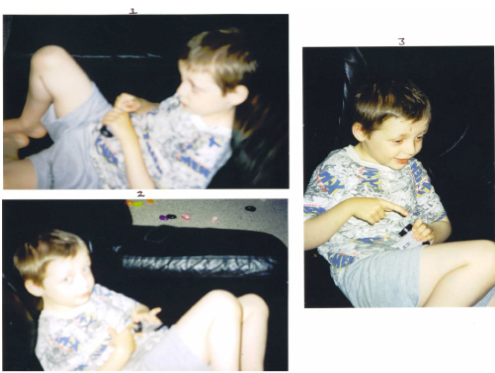

Autistic children continued to spin while looking elsewhere... as shown in the pictures below.

In the first set of pictures, Zachary was almost 5 years old and he was watching television. In the second picture, he was more fascinated by the fact that mom was taking yet another picture. In the third picture, Zachary was looking at something on the floor as he continued to spin. The second set of pictures was taken when Zachary was only 2 years old... yet the pattern was the same then too.

The love of spinning was clearly present, as was the fascination with a specific part of the spinning object. Again, Zachary's attention was primarily with the inner part of the wheel when it was a wheel that was the object of the spinning activity. Again, eye contact was easily broken with the spinning object, as clearly shown in the second picture. If you look closely, you could see Zachary had a small car next to him as he sat in the plastic bin. The small car was flipped over as he spun the wheels... looking about the room - happy as a lark!

These pictures clearly indicated that there was more to spinning than simply the fact that it provided a "visual stim". So, if a visual stim was not the answer - at least not the whole answer - as to why autistic children spinned... what was?

It was my firm belief that this activity was simply an "order fix" and stemmed from the autistic child's inability to process the "partial". Spinning was but an attempt at making the partial whole again.

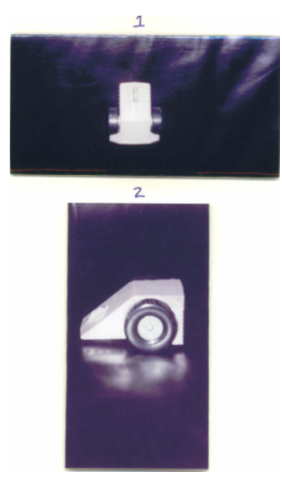

Before going into greater detail on what I believed was going on when an autistic child spinned, it was important for me to provide for you a description of the object Zachary was holding at almost age 5. This object illustrated the point quite well... although the same was true of pretty well all objects Zachary spun. This particular object, however, was the object that truly helped me to understand and so clearly see what was going on with this issue of spinning. This object was pictured below:

UPDATE Dec. 2005: The black wheels on this little toy also make a "clicking sound" much like gears changing... not sure if that is part of the fascination also with issues of "spinning" but I wanted to mention that since it was something I only very recently noticed when my son took this toy out once again to play with it... you actually have to have your ears very close to it to hear this clicking sound made by this toy... at least I do. :o) Most of the other things Zachary would spin did not have that sound... so... I still think there is more to it than the "sound issue" but I wanted to mention it anyway.

This was a little "car thing" I had purchased one day at McDonald's. It was part of the McDonald's Happy Meal that week. We had gone there to play on the equipment. Zachary could not eat anything in the restaurant due to the fact that he was on a casein free and gluten free diet. I often took Zachary to McDonald's just to play - to see how he interacted with other children. When he saw other children with this toy, of course, he wanted one also. So, I purchased the toy without the meal.

There were a few interesting characteristics about this toy that readers needed to take notice of. In the first picture, you can clearly see the toy had 2 large wheels with treads, and a smaller "wheel looking thing" in the middle of the toy. That small "wheel looking thing" in the middle of the toy had a "raised surface on it" that looked like a railroad track - but with only one rail positioned in the middle of the track. In addition, if you looked closely at the larger wheels, you could see that they had elevated "bumps" in the middle... to represent wheel studs. There was a larger one in the center, and 5 smaller ones around the larger one... they were barely visible on this picture, but they were there. The wheel studs of this toy created the interesting illusion of appearing to “go backwards” or in the direction opposite that of the spinning motion (see section on Motion for more on this issue).

This was where things became quite interesting... the focus of Zachary's attention was clearly with the wheel studs in the middle of the wheels – the parts to a wheel - parts to a whole. It almost looked as though he was trying to "pick them out" of the wheel... to get rid of them. In the second picture, note also the positioning of the fingers, on the wheel studs and the wheel treads. Also note that Zachary's first preoccupation was not with the activity of spinning, but rather with the wheel treads and wheel studs... the parts to the whole.

Zachary tried to "pick out" the wheel studs for quite some time... unable to do so, frustration set in and spinning started...

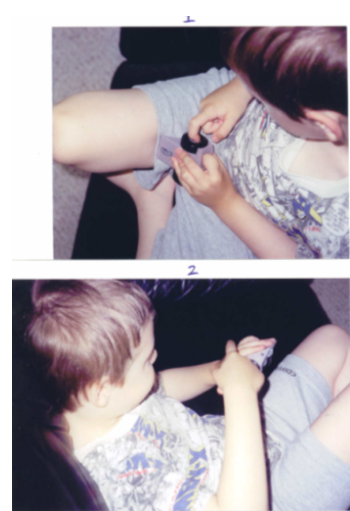

At this point, I asked Zachary to "stop spinning"... not willing to do that, he got off the couch - where he had been watching a movie - and resumed his spinning activity on the carpet. By then, I had noticed that Zachary only spun the big black wheels... he never tried to spin the little "wheel looking thing" in the middle of the car - so, of course, I asked him to spin the "small wheel" in the middle. His response surprised me... he stated: "no... no spinning small wheel". He then proceeded to do something else that was rather interesting...as depicted in the pictures below. I took the object and tried to spin the small middle wheel for him a few times in order to see his reaction. As I did this, Zachary kept saying: "no... no spinning small wheel". Once I gave him back his toy, he immediately physically positioned his thumb onto the "small middle wheel" to totally prevent it from spinning... and resumed the spinning of the large dark wheel.

This was quite interesting to me. I took the toy car from him, and inspected the "small middle wheel" a little further. I again tried to spin this "middle wheel" myself. This time, however, I noticed it could not physically be spun fast enough to make the "raised surface that look like a one rail track" disappear. As I tried to spin this "little middle wheel", Zachary, in a very assertive voice shouted: "Stop spinning". He became frustrated by my attempt to spin the small wheel. I then gave Zachary the car toy again to see what he would do if further prompted to spin that "small middle wheel"...

Zachary simply took the car and started to push it along the floor. Well... there was a time where I would have been thrilled to see him do this... thinking he was actually using a toy appropriately... pushing a car. To society, this was "normal"... socially acceptable behavior. Zachary, however, had simply figured out that I allowed pushing cars... even when I said "no spinning"... because "pushing cars" was considered socially acceptable. This time, however, it took very little time for me to realize that even this "pushing of the car" was not "normal play" at all because Zachary's eyes were still very much focused on those wheel studs as he pushed the car along the floor. Again, he could easily break eye contact with the toy if I did something to result in his breaking eye contact with the object of interest. By this time, I was convinced that spinning was not a behavior the autistic child engaged in primarily for a "visual stim"... it was something else.

Zachary then figured out that he could take his toy car and have the wheels spin as he turned his Sit'N Spin. So, I let him do that for a while, to the point, where eventually, the Sit'N Spin was going full speed as was the black wheel on which Zachary was so focused.

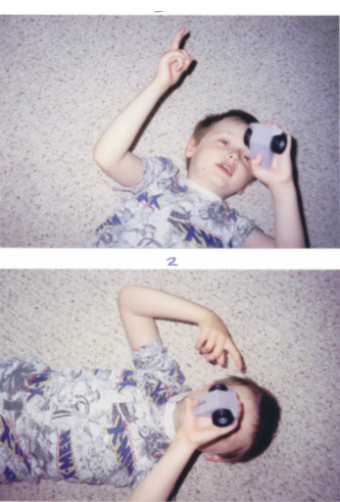

After this particular activity, Zachary was exhausted and went back to the couch to watch the rest of his movie. He placed the toy car next to him as he lay on the couch... and again, those wheel studs were positioned in his direct line of sight, as shown below. Although he was exhausted, Zachary was still somewhat restless, and for a short while, moved from one end of the couch to the other... moving the toy car and positioning the wheel studs each time he moved, again, in his direct line of sight.

I soon realized that the inability to process partiality was at the root of the autistic child's fascination with spinning. Spinning, if you think about it, does something that few other activities could do... it could create a visual impression that allowed the parts to become "the whole". As the toy car was spun, the wheel studs disappeared and became part of the whole. Since the "small middle wheel with the raised surface" did not spin fast enough to produce this illusion of the part becoming the whole, Zachary refused to spin it and in fact, did all he could to prevent even me from trying to do so. That particular "small middle wheel" was still very much a source of frustration for him.

This was a critical key to the autistic child's love of spinning... spinning made the parts become part of the whole... made the parts no longer easily distinguishable from the whole. It was important to note that "a part" could be as small as a "spec" on an object - it needed only be "something" the child did not perceive as belonging there... as a "natural part" to the whole. The inability to understand the whole without first understanding the parts, was completely in line with what was observed in spinning. Until the child understood "the parts" - in anything in life - and how they "made up the whole", “parts” would continue to be a source of frustration for the autistic child and would continue to make him seek coping mechanisms, such as spinning, to help him deal with the frustration that resulted from those things, those "parts" in his world he could not make sense of.

This also explained why eye contact was not always necessary. Motion, I believed, played a role in spinning (see section on Motion), but "just knowing" that the part was becoming a part of the whole as an object spinned was surely comforting to the autistic child... putting his world "back in order"... providing that "order fix" he so desperately needed to cope. When Zachary could not physically find something to spin, he simply pretended to be spinning something with his finger "in the air" or on my cheek... that alone provided great comfort for him.

This issue of the partial and the whole also explained why the autistic child was so fascinated with ceiling fans. If the fan was not moving, the child showed very little interest in it or begged to have it turned on. Most ceiling fans had 4 to 5 blades. As these began to spin, the blades "disappeared" and became part of a whole entity... no longer easily distinguishable from "the whole".

This also explained why even "odd" objects were spinned by the autistic child, such as irregular puzzle pieces. It did not matter what shape the object was... once it started spinning, the parts became part of the whole, resembling a circle even though the original shape could be rather "odd". Even with "odd shapes", the illusion of a complete circle was formed by the spinning of the object. In addition, there was a blurring of any design on a puzzle piece so that it became fully integrated into the whole again, eliminating any "parts" that could not be understood or properly processed by the child... and that was why the autistic child loved to spin.

I could think of nothing else in the autistic child's environment that could provide this necessary coping mechanism to cope with issues of partiality. Spinning, an activity so characteristic of the autistic child, was truly explained by my theory that the autistic child could not properly process the parts to a whole and that it was the inability to understand the "whole" without first understanding the "parts" that resulted in tremendous frustration for these children.

Spinning provided what no other activity could do... it made the "parts" become indistinguishable from the "whole" and as such, spinning was but a coping mechanism - the perfect "order fix" for the autistic child - his perfect way to cope with partiality - to make the partial whole again! :o)

I also believed there were issues of motion involved in the autistic child’s love of spinning. For more on that, see the section on motion.

Self-Spinning

Another area I came to understand a little more had to do with "self spinning"... something I still see in Zachary to this day. Zachary often looked up to the ceiling or down at the floor and he "spun himself". Was this his way of attempting to figure out how he himself fit into the "whole"... the environment? After all, persons were, like cars, moving "parts" to the world and perhaps Zachary simply could not understand how he, personally, fit into that whole... the environment, much in the way, I believed he did not understand how cars, these "other moving objects", did not fit into the whole! Self-spinning was simply Zachary’s way of attempting to “decode” how he, himself, fit into his world!

Other “Odd Behaviors”… In General

There are countless odd behaviors in autistic children that parents just cannot seem to explain.

The key to these "odd behaviors" as in spinning, was again in the autistic child's need for order and/or completeness and his need to understand the parts before the whole could make any sense. As with all behavior in my son, I found things got very easy to understand and control once I simply "knew the issue". In Zachary, I easily identified over 60 “odd behaviors” I could now explain based on issues with the proper processing or integration of the “parts to the whole”.

I noticed how this one function helped explain not only the odd behaviors themselves, but what was going on "within the odd behavior". For example, the whole issue of "the interrupted task" and the constant need to "start all over" was now explained also.

There were literally dozens of behaviors in my son, Zachary, that were explained by my theory that the autistic child was unable to properly integrate "parts" or “in betweens” into the whole. Below, I provided close to 60 examples of such behaviors for all readers...but, again, there were many, many more such examples (these were just the very obvious ones). This realization - in terms of the inability to properly process partiality - I came to only a short time ago. Although Zachary still had some issues with certain behaviors, I hoped that as I spent more time with him, working on specific problem areas, teaching him coping mechanisms and providing those all so valuable labels, that the majority, if not all these behaviors would soon become non-issues for him. The simple fact that the autistic child devised his own coping mechanisms over time, allowed me to take the positive in these coping mechanisms and use them to my advantage. As I labeled “more things”, more “parts” to the world, Zachary’s frustration levels continued to decrease. My theory of partiality processing also explained why for some children the extent or "degree" to which many of these odd behaviors were a problem varied so greatly. Each parent, unknowingly, had provided for his child coping mechanisms by the simple use of labels at various times... and in various situations - thus explaining the variation we saw in these children.

In addition to labeling things, teaching Zachary the concept of fractions greatly helped with many of these issues. After labeling, fractions were perhaps the parent's greatest tool in helping an autistic child deal with issues of partiality since fractions helped the autistic child understand that "parts" make up a whole and that once labeled, even "parts" became entities in and of themselves. For Zachary, understanding this concept provided a huge coping mechanism for a world that so often did not seem to make sense.

Zachary’s odd behaviors, as outlined below, I noticed tended to show up more when Zachary was idle. This issue was addressed in my section entitled: When Rest Is Work Too!

Zachary’s Odd Behaviors Explained By Issues In Partiality Processing

Putting clean and dirty dishes together in the dishwasher or sink - to Zachary, they all belonged together... dishes were dishes. Zachary could not understand "the difference" between the two unless the "parts" (clean verses dirty dishes) were first explained. To Zachary, all these "things" (dishes) belonged together and there was no need to separate them. Indeed, to separate them led to the creation of "parts" that made no sense when separated from the whole. Labeling dishes as clean or dirty and actually showing Zachary the difference between the two made all the difference because now, two separate "entities" or "parts" existed... clean dishes... and, dirty dishes. Clean and dirty dishes were no longer an issue for Zachary. An "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Putting my basket of clean clothes in with the basket of dirty clothes... if a basket was not around and there were dirty clothes in the washing machine, Zachary would take clean clothes, even taking them out of dresser drawers and put those in the washing machine too. Again, to Zachary, clothes were clothes... and they all belonged together. Again, I found the key was simply in labeling and showing him the difference between "dirty clothes" and "clean clothes". In order to do this, I showed Zachary stains on dirty clothes and actually made him smell dirty clothes and clean clothes to help solidify the concept that they truly were "different". To stop Zachary from putting all the dishes together, clean and dirty, or all the clothes together, clean and dirty, all I had to do was label "these as dirty" and "those as clean" ... I showed him the difference in the laundry by making him smell "stinky" clothes verses clean clothes as I said: "these are clean clothes" or "these are dirty clothes". When he wanted to put in one big pile all the clean laundry I had folded, all I had to do was label the piles: "a pile of towels, a pile of socks, a pile of dishtowels" and so on. Once Zachary had a label, he could see each pile as its own separate entity as opposed to being part of "all the clothes" and he no longer had to put them all together. Clean and dirty laundry was no longer an issue for Zachary. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Taking bandages off his skin, or scratching off scabs on his skin... to Zachary, the bandages and scabs were not "part of" the skin and as such, they did not belong there since they were not "part" of the original "whole" (the skin). Again, the key here was simply to show Zachary that these things were entities in and of themselves and to explain their purpose. Zachary still had some very minor issues with "things that did not belong on the skin", but he was much better than before. I found he could better tolerate a bandage on his skin in particular places. Bandages on the face, for example, were less tolerated than bandages on the leg. I believed there were "sensory issues" at play with the sense of touch... although these issues had greatly improved since Zachary had been on digestive enzymes (see section on First Steps For Parents!). Given the progress Zachary had made in the last 6 months with overall sensory issues as they related to touch, I expected this issue to be completely gone in the near future. Another two "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Peeling labels off cans, peeling stickers off everything. Again, these were not part of the "whole"... they did not belong and as such had to be removed. Labeling these things as "labels" and "stickers" almost completely did away with this issue. Zachary no longer removed labels from cans. He did remove stickers once in a while... especially when he was bored, but then, so did normal children. :o) It used to be that all stickers were removed. That was no longer the case. Many behaviors in the autistic, such as the removal of stickers, were also behaviors in normal children... the difference was really one of "degrees" or "how much" of a particular behavior was done. Another few "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Putting all his toys in a stack, or aligning them perfectly. In the past, this was always an "all or none" activity... no toy could be left "apart" from the stack (the whole) and all had to be perfectly aligned. Zachary was literally trying to similar objects together – to “connect” the parts. For example, he aligned all his pencils… or tried to stack them… he stacked puzzle pieces, flashcards, etc., to figure out “how the parts to the whole fit together”. For items in the house, this was now barely an issue… especially for those items that Zachary now understood in terms of their “purpose” (like the fact that pencils were used to write). As with other behaviors, the aligning and stacking of objects tended to surface more if Zachary was "idle". The perfectness once required and the intensity with which Zachary once performed these activities had also both been greatly reduced. More "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Putting all toys in the sandbox... or throwing them all out. One or two toys could never be set apart from the rest. Things on the lawn, such as sprinklers, the dog dish, etc., were also perceived as things that were not "part of the whole" and hence, had to be removed and "thrown away". Another few "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Filling the bucket in the sandbox... it had to be completely filled and dumped... the sand was either in or out... the bucket was either full or empty... there could never be an " in between" in terms of the fullness of the bucket. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Turning all lights either on or off ... Zachary could not have some off and some on at the same time. This, too, was much less of an issue for him compared to what it once had been. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Opening or closing all doors... again, he could not have some open and some closed at the same time. Also, if a door was opened, it had to be opened all the way... no "partially" opened doors were allowed. Another two "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Car windows had to be all up or all down... a partially opened window, either in the house or in the car sent Zachary screaming from the top of his lungs. I had now come to realize that although "biting" seemed to increase with the intake of phenolic foods (i.e., apples, bananas, tomatoes, raisins/grapes, etc.), "biting" in the autistic child was also very much a coping mechanism. This coping mechanism of biting I clearly saw in Zachary. When frustrated by my partially open living room or bedroom windows - things he could not "spin" - he simply resorted to biting to deal with the frustration of the situation. The result of this "biting" in an attempt to deal with the frustration of a partially opened window was evident in pictures provided in my section on "Biting". A few more "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Putting snow chunks back onto the snow bank after the plow had passed... all chunks (parts) belonged with the whole... the snow bank. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Separating flowers from their stems... to Zachary, stems belonged together, and flowers belonged together... there could be no "mixing" of the two. When Zachary picked flowers (dandelions), he immediately proceeded to ripping off the tops and throwing both parts away. It took a very long time for me to show him the concept of a "bouquet" and to actually have him be able to take flowers home in a bunch. Yet, even once home, in no time, I found Zachary separating the flower from the stem and making a "pile of flower tops" and a "pile of stems". The "flower" (flower + stem) was not perceived as a whole until labeled as such. To call a plant: "a flower" was confusing to Zachary. He thought only that "top part" was the flower and did not see the stem as a part of the whole until I literally pointed out that "a flower" was "the flower + the stem". Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Wanting to pick all the dandelions while on a walk... again, he felt they "all belonged" together. This made for very slow, and very short walks in terms of distance, yet very long walks in terms of duration. Much as was the case with "snow chunks", it could take close to an hour to make it but a few feet from our driveway. Luckily, I finally stumbled upon the concepts of "too many" and "take some" to explain to Zachary that there were "too many flowers to pick" or "too many snow chunks to put back on the snow bank". Once labeled as "too many" and encouraged to take "some", this was no longer an issue for Zachary. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

All clothes had to be either on or off... again, no "in betweens". Zachary experienced great frustration if only partially dressed. This was true for many autistic children and why so many of them hated to wear clothing - especially, when very young and clothing had perhaps not been "defined" because clothing was not part of the whole... not part of the skin. I suspected some children had other “truly sensory” issues at play in terms of touch, but again, issues with partiality certainly explained many issues once believed to be “sensory” also.

Instead of simply "putting clothes on" Zachary, I came to label each piece as I put it on. At this point, Zachary had more issues with not having pants on... that was his big one right now. I have never really had problems with putting clothes on Zachary... I stumbled upon labeling them early on in life. Now, my problem was more that he did not like having his clothes off – especially his pants. Perhaps he had noticed that everyone wore clothes. I had also provided for him the “purpose” of clothes in telling him that he had to put them on not to be cold when he went outside. But, some aspects of this issue, I was still working on with Zachary. I knew that I could put shorts on him instead of pants... and that was ok... but he would not want to be without something on his lower extremities. He could more easily go without a shirt, however! I had some very specific thoughts on this issue with clothing when it came to Zachary’s preferences (see section on Potty Training for more on this issue).

This was still a small issue I needed to work on... not a "biggy" in my book that I was overly concerned with. I learned a long time ago not to "sweat the small stuff"... and wanting to leave your clothes on was "small stuff" in my book! Zachary was perfectly fine with tearing them all off at bath time! :o) But, again, at least in part, this too was an issue with "partials" and "completeness in everything"... for Zachary, for a long time, all clothes were either on or off... no "partial dressing" was allowed. Socks had to be both on or off. There could never be one off and one on. The same was true for shoes. To leave Zachary "partially dressed" like this created a sense of frustration for him. Yet, this was not something that would be particularly troubling to a normal child. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Constant running back and forth down a hallway. Zachary always had to run all the way down the hall and all the way back... never would he stop in the "middle" (unless forced to do so by a person standing in the way... but even then, he would practically tear you down to get by and complete the motion of physically getting to the other end). It was this type of behavior so many saw as "lack of discipline" or "lack of manners" in these children. I, however, now saw these behaviors as simply a part of the overall problem... the inability to cope with partiality in anything. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Turning all the pages in a book very quickly until the end was reached... never stopping to read or look at the information on a particular page. A book had to be "closed" to be perceived as an entity. Pages were parts to a whole that were not understood and as such, Zachary attempted to physically ignore them by either disregarding the information on the pages and flipping through them as quickly as he possibly physically could do so, and by actually running away if I attempted to force him to look at a particular page. He did the same thing with computer programs that were set up "as books" with arrows for "turning the pages". Zachary would incessantly "click on the turn page arrow" until the end of the "book" on the program was reached. He also did this for "non book" type arrows on computer programs that "moved the user along" through to the end of a task or program. Needless to say, this made teaching and learning a very, very difficult task. Labeling, again, provided a huge coping mechanism in that a book could now be seen as something with a "book cover" or "front", something that also had "a back" and something that had "pages" in the middle. Furthermore, pages were labeled as something "to read" or "look at". A few more "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Constantly wanting to scroll "all the way up" or "all the way down" while on the computer... again, no "in between" or pausing "halfway" was allowed. Another "odd behavior" explained by issues with the proper processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Constantly removing the toilet paper from the holder... they did not belong "together" as a whole. Nor did the toilet paper actually belong on the roll itself. Neither did paper towels, foil wrap, etc., belong on their roll... and therefore, they too, had to be "unrolled" at the first opportunity. To Zachary, the roll and “that stuff on it” did not belong together, and as such, they had to be separated. Another few "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Screaming from the top of his lungs if a song was interrupted or the radio was turned off "in the middle" of something. Songs on the radio had to be "completed"... they could not be left "partially done". What helped here was simply to tell Zachary "music off" or "radio off" to help him anticipate the fact that what he was hearing was about to end abruptly. The inability to process partiality also explained why autistic children seemed to absolutely love songs. In my opinion, there was more at play here than the simple "beauty" of a song. A song had a beginning and an end that could be perceived by the child as the words and/or music ended. As such, I believed this was the reason songs and/or music seemed to work so well in teaching some autistic children and why for the autistic, music may be even more relaxing than it was to a normal child. Music, in an of itself provided a coping mechanism... something that provided completeness as it flowed from beginning to end! Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Screaming if videos were turned off prior to full completion... especially if turned off during the captions or credits at the end of the movie (for more on "captions", see my section on Language). Again, the movie or the captions had to be "all done" before you could turn them off... you could not stop the video "in the middle", prior to its full completion! Rewinding the video with the pictures "going backwards" on the screen was extremely stressful for Zachary - resulting in screaming from the top of his lungs as he attempted to deal with the frustration this created in his world. To Zachary, normal "order" was "forward"... he knew nothing else... until the word "rewinding" came into his life. That word helped him to understand that this "going backwards" was actually called something... and that something, by the simple act of tagging a label to it, now became an entity in and of itself. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Spilling/tipping over of cups or containers only partially filled... yet, showing no interest whatsoever in cups and/or containers that were either completely full, or completely empty. Cups and containers had to be "all full" or "all empty"... no "in between" or "partial" was allowed. If I left a cup of coffee partially drank on my desk, Zachary, immediately upon perceiving this "offending object", in an almost "automatic manner", as soon as he saw the "partiality", flipped the cup quickly over, spilling the remainder of its contents. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Fascination with trains/puzzles. This, too, was easily explained by issues with the proper processing of partiality. Putting pieces together - puzzle pieces or train pieces - created a whole... and did away with the partial. Trains were especially fascinating since the train provided for the creation of a whole by putting the parts (train cars) together... and gave the added benefit of wheels in motion ... the spinning... something that also made the partial whole. Leaving one piece of the puzzle or train "out", however, sent Zachary screaming. More "odd behaviors" (odd, here, primarily due to the extreme fascination and to the degree to which these activities were engaged in) very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Love of putting things together... of any "mechanical" type object... and the almost insatiable desire to try to figure out "how mechanical things worked". Prior to Zachary's diagnosis, I used to joke with my husband that, surely, Zachary would someday be a mechanical engineer. He was always looking at "how things worked"... looking at the mechanics of most physical objects... pulleys, levers, gears, etc. - all these things fascinated him. Little did I realize that the fascination was with seeing how the parts formed “the whole”. With physical objects, "seeing how things worked" - physically - helped Zachary make sense of his world. And, this was true of the great majority of autistic children. Their fascination with the specific details of physical objects is one readily explained by their need to understand the parts to fully understand the whole.

It was when "the physical" was not as readily available in terms of how parts fit into the whole that frustration set in and life fell apart. This was especially true for abstract concepts such as conversation, socialization, process completion, etc. (see section on Teaching Language, Socialization and Teaching A Process). But, when parts could physically and especially, visually, be put together, things made more sense for the autistic child. This also explained why the autistic child attempted to always use "all parts or all pieces" before him... he was constantly trying to put the parts into a whole that made sense.

In anything where the parts could be put together to form a whole... there was enthusiasm and delight... in everything else, there was frustration and confusion. As the autistic child developed more coping mechanisms over time, as more labels and words defining quantities were understood, fewer pieces were necessary to understand the whole and cope with partiality in everyday life (see sections on Fractions, Words Defining Quantity and Words To Cope). More "odd behaviors" (odd, here, primarily due to the extreme fascination and to the degree to which these activities were engaged in) very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Walking the white line on the side of the street when we went for walks - unwilling to walk "off the line"... the line provided a whole - as well as an order to direction. This behavior, I now refer to as "walking the line". For more on this, see section on Safety. This was a huge issue for parents of the autistic. Another "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Fearing certain sounds and the putting of hands on ears when unexpected sounds were introduced. Again, sounds were "parts" to the "whole"... and when a "new part", such as a loud, unexpected sound was introduced, Zachary would put his hands over his ears immediately. As soon as I labeled the "new part" (i.e., it's a broken muffler, it's a P.A. system, etc.), Zachary was better able to cope with the sound... both at the time he actually heard it and also in the future, when he heard it again, unexpectedly. In the future, whenever he heard a loud truck or car, he - himself - would simply say: "broken muffler"... and he no longer had to put his hands on his ears. He now understood the sound and it no longer provided a "new part" to the information he needed to process in his environment... the label had made it such that the once "unknown" and "unexpected" sound had been incorporated into the whole... everyday sounds of life.

I wanted to emphasize that I did think there were definitely other issues going on with auditory processing - issues that were “truly sensory” in nature (i.e., physical damage to the ear or the auditory nerve). I did believe that certain sound frequencies may actually cause pain to the autistic. The reason I say this was due to the fact that since on enzymes, Zachary, overall, was doing much, much better in the area of auditory issues. There was once a time where he would actually cry when he heard high frequencies... showing actual physical pain in his facial expressions. This was something I now saw only very rarely. Zachary was much less sensitive to noises overall and was now fine with removing his earmuffs in most stores. More "odd behavior" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything. For more on this, see section on Auditory Issues.

Note: In my opinion, buying earmuffs for Zachary was one of the best things we did for him as we continued to work on auditory issues. This $10.00 investment made life much better for him by filtering out noises that were too offensive or unexpected.

Making a mess "as I was cleaning up". This was a particularly troubling and exhausting behavior for a very long time. For example, if I was picking up cards off the floor and placing them on the table - as I did that - and returned to pick more up, Zachary would throw the cards already on the table back onto the floor. To him, they could not be "separated"... they had to all be on the floor or all on the table at one time. This was true for countless objects. If "partials" existed anywhere, he quickly "resolved" the partiality by "putting things back together... in his own way"... even if that meant undoing everything I had just done. If objects were perceived as "parts" that did not belong together (see Fraction and Exercises I Do At Home sections), as quickly as he possibly could, Zachary physically scattered the "parts", putting as much physical distance among the objects as possible so that he could no longer physically/visually perceive these items as parts to a whole. More "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Taking the pillow covers off the pillows, and at times, sheets and blankets off the bed. Pillow covers, sheets and blankets were not "parts to the whole", the mattress... they did not belong there. More "odd behaviors" very much explained by issues with the processing of "partiality" and the need for completeness in everything.

Pushing on body parts to make them "even" or "in the same position". For example, Zachary would get very upset if, as I sat on the couch, I had one leg crossed over the other. He would come up to me and try to put them both in the same position. The same would be true if I was on a bed, on my back, with one leg straight on the bed and the other positioned so that my knee was bent and my foot lay flat on the bed. Again, Zachary would "push down" on the knee that was raised until his weight forced my leg to go down flatly onto the bed... just like the other leg. The same was also true for arms. Labeling positions (i.e., I have one "bent leg") was the best way to help with this issue.

A behavior I once observed in my autistic nephew, Andrew, while in my home could also be explained by issues with partiality. Andrew had an extreme concern over the fact that he had a loose tooth... a part of the whole was about to be removed and as such, he became very distressed by it... to the point that this "loose tooth" was almost all he could think about for an entire day... it became the object of his complete focus – obsessively so!

Zachary, himself, however, had countless other behaviors that could now be explained by this inability to properly integrate the parts to the whole. Taking all the utensils out of the utensil tray in the kitchen. Again, these things were not "part" of the tray... they were not part of the whole. Zachary could not see "how they fit together" and as such, they had to be physically separated. The same was true as he took clothes out of dressers, clothes off hangers, pots and pans out of cupboards, soap out of soap dishes, pulled apart lamps, pulled apart countless leaves to separate the "veins" from the rest or "green part" of each leaf, pulled bark from trees, pushed countless rocks off pavement, tried to scratch off paint markings and "cracks" on the road, pulled ropes apart into individual threads, pulled wires apart (the enclosure or casing from its contents), pulled upholstery materials from inside couches, quilts, chairs - anything, tried to pull buttons off shirts, pulled a new small hole off his pants by picking at it so much that his fingers went through the hole and allowed him to then rip the pants, literally, completely apart, pulled individual threads in clothing apart, pulled carpet threads apart, emptied the trash from the trash can, tried to pull hairs - one at a time - from one's head, pulled growing plants from the garden, ruined countless videos and audio tapes as he pulled the tape from its enclosure, pulled countless CD cases apart, scratched and destroyed countless CDs on the floor or by biting them in an attempt to do away with the writing/labeling on the CD, ripped countless papers because text could not be perceived as part of the whole - the sheet of paper, emptied anything partially full - again, a huge issue in terms of possible danger for a child in terms of any toxic materials in any container and in terms of medicine. I have no doubt that if a medicine container was opened, the autistic child would not stop at one pill... the entire bottle would have to be eaten... the improper functioning of partiality in the autistic child's brain would certainly ensure that - and Zachary had, amazingly, figured out how to open child-proof containers at a very young age. Hence, I placed all medicine in a locked toolbox and hid the key.

This theory also explained why autistic children apparently had no fear of danger. Cars on the street were not properly perceived... they were not considered parts to the whole (the street) and if not properly perceived, and recognized as entities in and of themselves, and identified or labeled as objects of "danger", then the autistic child had no fear of them. Cars had to be identified as part of the whole. The child had to be made to understand that "streets were for cars - not people", "that streets and cars went together", that "cars were very dangerous" and that "you do not go in front of or in back of cars", that "you stay away from cars". Safety issues such as these, I believed had to be repeated, in multiple ways, in multiple situations to make the child understand all aspects of safety as it related to the situation (see sections on Safety and Motion also for more on this critical issue).

When it came to the autistic child, I feared issues of safety were very situation specific. Again, this was a very serious issue for parents and society as a whole. How can one possibly teach a young child "issues of safety" when that child cannot first understand the "parts" that make up the "whole"... in this case, the dangerous situation? As with everything for the autistic child this was something that primarily would come to be understood over time, as the child learned more and more about his environment, as he was provided with more coping mechanisms (i.e., labels) to more fully understand that environment. For the very young autistic child, this indeed was truly an issue of life and death.

This inability to understand the parts to the whole when combined with a dangerous situation indeed made for a deadly combination! This explained why Zachary once ran out right in front of an oncoming car in our front yard while we were raking leaves. He was playing quietly... and before I knew it, he was off and running down a small hill, into the street and straight into the path of an oncoming car. Luckily the car saw him and was able to stop in time. Yet, Zachary had not perceived the car as a part to the whole!

This also explained why recently, while on my in-laws farm, as his father and I worked, Zachary headed straight for a bull pen... he started walking down the "shoot" and had that door been opened to the bull pen or the latch opened, without a question, he would have gone in - the "shoot" leading to the pen was part of the whole (the pen), the bull inside the pen, however, was not... and as such, Zachary did not perceive it as a part to the whole... a very dangerous part... and as such, the "danger" was not perceived. The bull itself would have had to be labeled as "a bull" and then the label of "bulls are dangerous - stay away" would need to follow. For more on this issue, please read my sections on Safety and Motion - a must read for all parents of the autistic! The inability to perceive danger - another issue explained, yet again, by the inability of the autistic child to properly process the parts to a whole!

Screaming when changes in direction were perceived. To Zachary, normal order was "forward"... only that made sense...he knew nothing else. People and cars went forward... that was "normal" in life, and anything else created immense frustration. We often traveled at night due to Zachary's autism. But, on one occasion, we had decided to leave in the morning, after Zachary was awake. Zachary was about 2 at the time and we lived in the suburbs of Chicago. When we took an on-ramp to get onto the highway leading north to Milwaukee and Canada, Zachary noticed the change in direction and it upset him tremendously. He screamed and cried almost nonstop for 7 hours. No matter what we did, nothing could console him. We were 5 hours from home and the rest of the family could no longer bear the crying and screaming. Zachary was nonverbal at this time... his vocabulary consisting of perhaps 4 words. We decided to turn back... we just could not tolerate the very likely probability of an absolutely horrible vacation. As soon as we "turned back" and Zachary perceived we had turned around, he instantly stopped screaming. At the time, we were so thankful for the quietness that we failed to see what had caused it. We kept expecting the screams and crying to start over at any time. We were exhausted and anxious to get home. There would not be a peep from Zachary all the way home - for the next 7 hours. Zachary had no idea we were "heading back home"... we had simply agreed to "turn around". All Zachary could have perceived was the "direction change". I would later come to realize what a huge issue changes in direction truly were for Zachary... so much so that it very nearly cost him his life! I encouraged all parents to learn more about this very important issue by reading my section on Safety.

Zachary truly had serious issues with direction changes - until directions were labeled as "left", "right", "backwards" or "sideways"... in everything... from car rides , to walks, to rewinding of videos ("going backwards"). Yet, once labeled, and identified as an "entity in and of itself", these other directions were now "ok". This issue was a little harder to understand in terms of "partials", but if you think about it, the concept of "direction" was an entity in and of itself. "Normal direction" was going forward and as such, any change in direction would be perceived as breaking from the whole... from what was previously known as an "ordered" way to go... going forward only "made sense" and was "orderly"... this was the only "part" to direction Zachary seemed to understand... it was "normal" direction. All these other directions (left, right, sideways, backwards) brought an unknown dimension or "part" to the process of direction, and as such, they were not tolerated. Although a little more "abstract" in nature, the issue of problems with changes in direction, also can be explained based on the inability to process partiality... the parts to the whole... in this case, direction.

As far as "rocking" was concerned, this was a behavior I never saw in Zachary although I knew it was one found in many autistic children. Having never been able to actually "observe" a rocking situation... to see what happened just before the behavior started, etc., I can only guess that perhaps this was simply another coping mechanism for the child... another way to deal with the stress of his daily life. Again, this was simply a guess on my part, but, I suspect, perhaps a good one. Even normal children find comfort and security in "rocking". :o)

Many of the above behaviors become “obsessive” for the autistic child. Obsessive compulsive behaviors, to some degree could be explained, again, based on the autistic child’s inability to properly cope with partiality… to understand the whole without first understanding the parts that made up the whole.

I had once heard a young man speak of his life with obsessive-compulsive disorder. This young man was approximately 17 and had no other "label"... he had not been labeled as autistic. As he talked he explained how he felt he could "catch germs everywhere" and that as such, he constantly had to wash his hands. If you think about it, much in the way that a bandage was quickly removed by the autistic child who had not had a bandage labeled, a child who had not learned to cope with something (the bandages) that was not part of the whole (the skin), so too would a person suffering from obsessive compulsive behavior attempt to "remove" something (germs) that were not part of the whole (the skin or person). It was my belief, that in the autistic, repetitive, obsessive-compulsive behaviors could often times be explained by the need to make something whole and to “do away” with the parts that were perceived as “not belonging”.

The one behavior still very troubling to me was that of Zachary's pushing of his forehead along the floor. I can only suspect that Zachary may have been experiencing physical pain as he did this, perhaps suffering from an intense headache. I, personally, did not believe the issue of headaches in the autistic had been given enough serious attention, although some studies did seem to suggest that headaches, such as migraines, could result from neurological stress. If this were true, this could explain this particularly troublesome "odd behavior". I believed this could be what was at play when it did occur so often... when Zachary was first diagnosed with autism. There was a chance that the issue with "forehead pushing along the carpet" could be sensory in nature, perhaps having something to do with auditory processing and the angle of the ear, but my instincts told me that pain, specifically in the form of a headache could better explain this “odd behavior”. This behavior had basically disappeared in Zachary, surfacing only very rarely. For parents who did see this behavior in their children, I encouraged you to try to determine if your child had a headache... although I knew this would indeed be difficult to do - especially when the child was nonverbal.

In closing this section on "Odd Behaviors Explained", suffice it to say that I could easily list over 100 "odd behaviors" that I can now fully explain based solely on the inability of the autistic child to properly process partiality, but time necessitated I move on to "other subjects". :o) I hoped that what I had listed here, however, would be enough to show parents that partiality was truly an issue for every autistic child, and in my opinion, was at the heart of 99% of their behavioral, social, communication, and emotional issues as well as at the heart of many sensory issues, too.

Autistic children had quite an array of "odd behaviors" and indeed, if parents started to think of "odd behaviors" in their own autistic children, I was sure those "odd behaviors" they saw also would have deep roots in the inability to properly process partiality.

The key to extinguishing these "odd behaviors" was in helping the autistic child understand how the parts made up the whole and in defining the “purpose” behind everything... and the best way to do that was through the use of labels, explanations, the concept of fractions, words of quantity, words to cope, etc. I found the best way to deal with all these issues mentioned above was simply to make use of labels. Labeling and explaining everything provided a "whole entity" for the partial... making each part a whole in and of itself. Labeling and other coping mechanisms were further addressed in other sections.